Snow History: Telephone Special Train

The frozen landscape and frigid temperatures this week have us reflecting on snowstorms of yesteryear. From the archives, we share an article excerpt that takes us back to a snow event in 1932.

But first, a slim history of the Harrisonburg Telephone Company which originated in 1899, when Rockingham County Sheriff John A. Switzer saw a need for quick and reliable communications around the county. After purchasing the Valley Telephone Company and other lines, he was in the telephone business. His deputy and son, Walter C. Switzer, eventually took over and grew the business until his death in 1924. At that time, Walter’s two young sons, decided to leave the business office of the Richmond Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Company (Frank) and the law school at Washington & Lee in Lexington, Virginia, (Fred) to carry on in their father’s and grandfather’s footsteps.

Not even a decade later, the young businessmen were profiled in the monthly periodical printed for the employees of the Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Companies, from which we provide this excerpt:

“One of the big pieces of excitement came along only last year [1932], when a sleet and snow storm knocked over most of their lines and the lines connecting with their switchboards, and also all telegraph lines, and completely isolated the county. Likewise, roads were blocked in all directions.

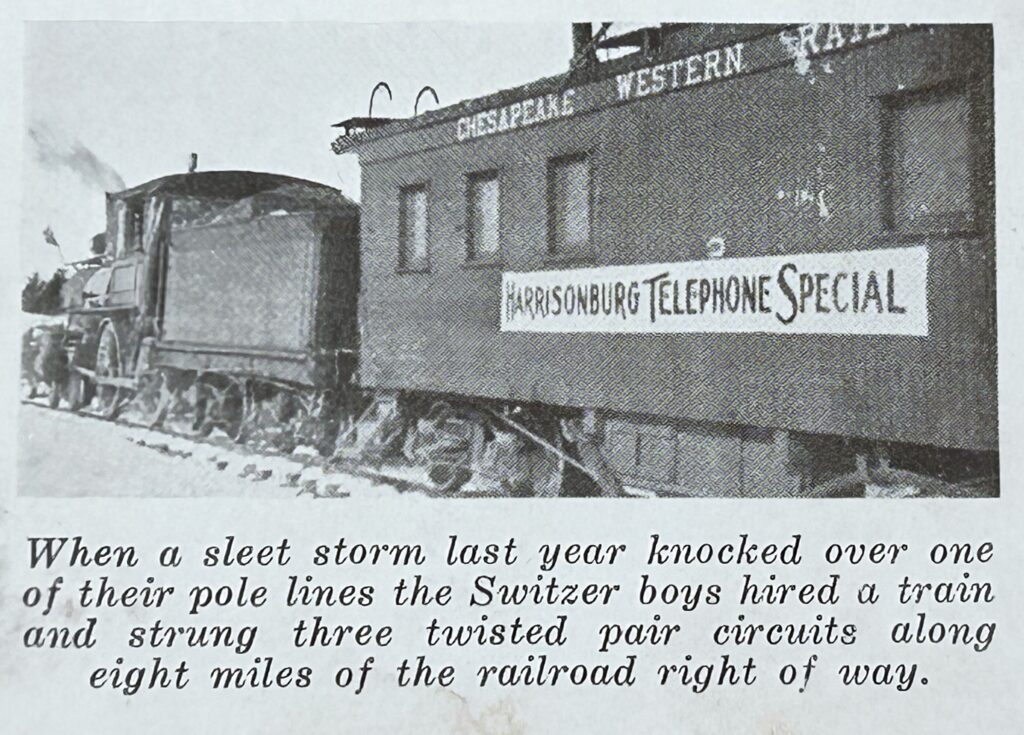

They secured the services of a local amateur broadcaster, Russell Main, and got him to broadcast an S.O.S. for telephone supplies. The air was filled at the time with radio messages from other isolated towns. Mr. Main’s message was finally picked up at Kearney, N.J., and relayed to Richmond and then to Roanoke, from which city a truckload of twisted pair and other material was started across the mountains. Meanwhile, they had used up all the twist on hand and the lines to Elkton were still down for a greater part of the distance. There is a small railroad, 25 miles long, which passes through Harrisonburg from the western part of the county and goes east to Elkton. The Switzer boys had an idea. They would hire a train and string twisted pair along the tracks. They secured permission to fasten it temporarily to poles belonging to the railroad company. They hired the train—an engine and a car—loaded it with the material which had arrived from Roanoke, also with men and a cook and a supply of food, and started out.

And here comes the most unusual part—the mother of the boys and both their wives insisted on going along. The Switzers were out to restore that service even if it took the entire family. Although the temperature was ‘way down and the work was strenuous, they actually made a picnic out of it. And in all the excitement they didn’t overlook the advertising value of what they were doing. They had a big banner painted and nailed on the side of the car. It bore just three words: Harrisonburg Telephone Special. They strung three circuits that way for a distance of eight miles and everybody was happy, and service was restored by 7:30 that evening.”

Excerpted from “Fred and Frank Switzer, Virginia Telephone Men,” by Oliver Martin; originally printed in The Transmitter, published and distributed monthly in the interests of the employees of the Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Companies, 725 13th St. NW, Washington, DC, Volume 21, August 1933, Number 8.