Circus Days Part 1

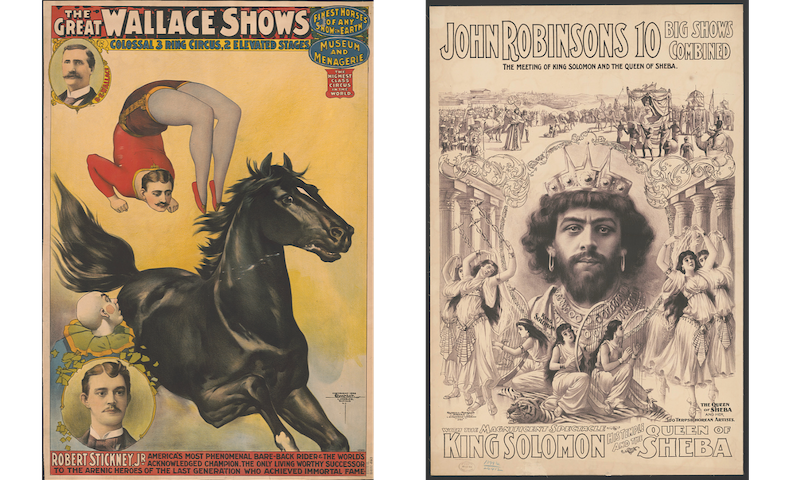

This photo takes us back to Harrisonburg’s court square as a circus parade traveled north on Main Street. Many signs clearly state AUG 24 as an important date. Zooming in, the date appears to announce Wallace Shows. Other signs show a larger 23. What is the story?

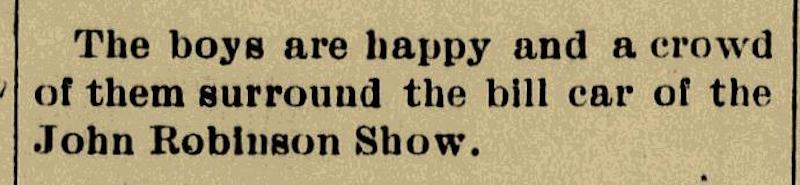

Searching for “Wallace Shows Harrisonburg” began a remarkable investigation of circus history which revealed the business of advertising and the rivalry of the circus circuit in the late 19th century. The following articles will dive into the history surrounding those two days in August when the shows of two circuses came to town: Old John Robinson and The Great Wallace.

Part 1: Post No Bills

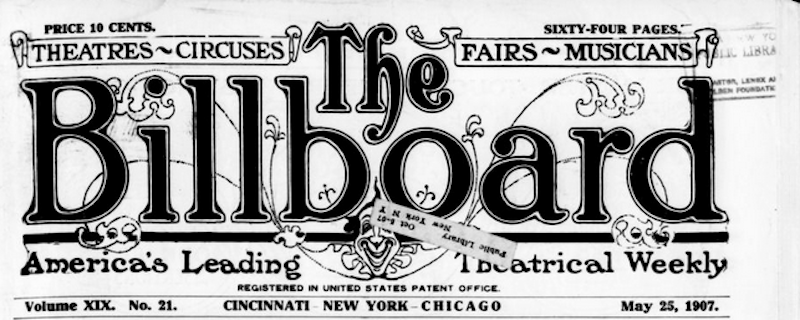

Before any exotic animals, “strong men”, and raucous clowns could roll into Harrisonburg in August of 1899, feats of another kind were witnessed all over town. Notes found in The Billboard: America’s Leading Theatrical Weekly reported that one William Mocerf single-handedly posted 906 sheets of paper over 39 miles within 12.5 hours to advertise the coming attraction. Mocerf, who was a bill poster for the Great Wallace Shows, broke the record for “hanging paper” which had been set by Harrisonburg’s very own Sam Braithwaite with 887 sheets.

Advertisements for tents dominate the industry news and gossip pages for Tent Shows. There are also listings for theatrical supplies: uniforms, paint, snakes, and other wild animals. Note the shout-out for “BILLPOSTING NEWS” through the Signs of the Times ad.

The banner ads and sandwich boards in Photo0748 are forms of outdoor advertising. Window displays (also seen in the photo) and billboards are other early examples. Note the baby elephant following its presumed mother.

Indeed, outdoor advertising was big business — as well as properly organized. As early as 1870, an Independent Billposters Organization formed and provided a needed code of ethics and industry standards. One argument for standards indicated that the actions of posting over anothers’ bills caused strife within the industry.

The popularity of the circus reached its heights in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In a time before motion pictures, circuses provided entertaining marvels and a window into the world far beyond a local community. Circus-goers could witness incredible feats of skill and daring, see exotic animals from distant lands, and laugh at the humorous antics of clowns. When the circus came to town, people celebrated the event like a holiday.

To build excitement and anticipation, circus companies sent out early publicity teams. Over several weeks, “Advance” cars promoted the upcoming shows. Like a well-branded FedEx 18-wheeler on the highway, the first “Advance” cars rode the rails proudly advertising their circus with a decorated, eye-catching exterior.

Harrisonburg Evening News, August, 16, 1899

Traveling inside were colorful stacks of various-sized bills (posters) and the men who posted them on windows, buildings, walls, and other available surfaces. The value of the paper on a car easily reached five to six figures. Following a week later, the second Advance team worked to cultivate newspaper interest and advertising. Bill “stickers” extended their work into neighboring communities. The third week, a car freshened the paper. We do not know where or when Sam Braithwaite set his billposting record. It’s possible that he rode as part of a second Advance team, or he may have been contracted locally.

A May 19, 1900 article in Billboard addressed these Advance operations:

Advertising contributes so importantly to the success of a circus that, from the general advance agent and special press representative to the meanest bill poster, the work actually employs more men than there are performers in the “arena” when the “show” is “on the road,” says the “New York Evening Post.” One of the largest traveling circuses now in this country spends more than $200,000 in a season of 200 days, and employs 80 men for a much longer time for nothing but to announce its coming and boom its attractions.

Circus businessman W.C. Coup addressed the “prodigious” costs and challenges of circus advertising paper and distribution (Billboard, April, 1, 1900):

I think circus people would be better off if ordinances were passed wholly prohibiting bill posting; but unfortunately such a movement would go far toward breaking up a profitable industry, since many of the bill posters are rich men, some making as much as $25,000 a year, and a few fully $50,000.

Based on newspaper comments on the proliferation of paper, like this one from The Evening News, August 10, 1899, many communities would likely concur with such ordinances. And, it’s no wonder that in cities today we can still see telephone poles and vacant walls plastered – ironically – with signs that read “Post No Bills.”